Animal calls are not comparable to human speech

Jun. 26th, 2025 05:39 pmBut can they still tell us something useful about language? Here are two new papers that address that question:

I.

"What the Hidden Rhythms of Orangutan Calls Can Tell Us about Language – New Research." De Gregorio, Chiara. The Conversation, May 27, 2025.

In the dense forests of Indonesia, you can hear strange and haunting sounds. At first, these calls may seem like a random collection of noises – but my rhythmic analyses reveal a different story.

Those noises are the calls of Sumatran orangutans (Pongo abelii), used to warn others about the presence of predators. Orangutans belong to our animal family – we’re both great apes. That means we share a common ancestor – a species that lived millions of years ago, from which we both evolved.

Like us, orangutans have hands that can grasp, they use tools and can learn new things. We share about 97% of our DNA with orangutans, which means many parts of our bodies and brains work in similar ways.

That’s why studying orangutans can also help us understand more about how humans evolved, especially when it comes to things like communication, intelligence and the roots of language and rhythm.

Research on orangutan communication conducted by evolutionary psychologist Adriano Lameira and colleagues in 2024 focused on a different species of orangutan, the wild Bornean orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus wurmbii). They looked at a type of vocalisation made only by males, known as the long call, and found that long calls are organised into two levels of rhythmic hierarchy.

This was a groundbreaking discovery, showing that orangutan rhythms are structured in a recursive way. Human language is deeply recursive.

Recursion is when something is built from smaller parts that follow the same pattern. For example, in language, a sentence can contain another sentence inside it. In music, a rhythm can be made of smaller rhythms nested within each other. It’s a way of organising information in layers, where the same structure repeats at different levels.

Has wonderful videos. The orangutans sound like they're saying something. Listen.

Discussing "Third-Order Self-Embedded Vocal Motifs in Wild Orangutans, and the Selective Evolution of Recursion." De Gregorio, Chiara et al. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences (May 16, 2.

Abstract

Recursion, the neuro-computational operation of nesting a signal or pattern within itself, lies at the structural basis of language. Classically considered absent in the vocal repertoires of nonhuman animals, whether recursion evolved step-by-step or saltationally in humans is among the most fervent debates in cognitive science since Chomsky's seminal work on syntax in the 1950s. The recent discovery of self-embedded vocal motifs in wild (nonhuman) great apes—Bornean male orangutans’ long calls—lends initial but important support to the notion that recursion, or at least temporal recursion, is not uniquely human among hominids and that its evolution was based on shared ancestry. Building on these findings, we test four necessary predictions for a gradual evolutionary scenario in wild Sumatran female orangutans’ alarm calls, the longest known combinations of consonant-like and vowel-like calls among great apes (excepting humans). From the data, we propose third-order self-embedded isochrony: three hierarchical levels of nested isochronous combinatoric units, with each level exhibiting unique variation dynamics and information content relative to context. Our findings confirm that recursive operations underpin great ape call combinatorics, operations that likely evolved gradually in the human lineage as vocal sequences became longer and more intricate.

II.

"Animals Can't Talk like Humans Do – Here's Why the Hunt for Their Languages Has Left Us Empty-Handed." Jon-And, Anna et al. The Conversation, June 9, 2025.

Why do humans have language and other animals apparently don’t? It’s one of the most enduring questions in the study of mind and communication. Across all cultures, humans use richly expressive languages built on complex structures, which let us talk about the past, the future, imaginary worlds, moral dilemmas and mathematical truths. No other species does this.

Yet we are fascinated by the idea that animals might be more similar to us than it seems. We delight in the possibility that dolphins tell stories or that apes can ponder the future. We are social and thinking creatures, and we love to see our reflection in others. That deep desire may have influenced the study of animal cognition.

Over the past two decades, studies of thinking and language in animals, especially those highlighting similarities with human abilities, have flourished in academia and attracted extensive media coverage. A wave of recent studies reflects a growing momentum.

Two recent papers, both in top-tier journals, focus on our closest relatives: chimpanzees and bonobos. They claim these apes combine vocalisations in ways that suggest a capacity for compositionality, a key feature of human language.

In simple terms, compositionality is the capacity to combine words and phrases into complex expressions, where the overall meaning derives from the meanings of the parts and their order. It is what allows a finite set of words to generate an infinite range of meanings. The idea that great apes might do something similar has been presented as a potential breakthrough, hinting that the roots of language may lie deeper in our evolutionary past than we thought.

But there is a catch: combining elements is not enough. A fundamental aspect of compositionality in human language is that it is productive. We do not just reuse a fixed set of combinations; we generate new ones, effortlessly. A child who learns the word “wug” can instantly say “wugs” without having heard it before, applying rules to unfamiliar elements.

That flexible creativity gives language its vast expressive power. Yet while animal calls can be combined, nobody has observed animals doing this to create new meanings in an open-ended productive manner. They don’t scale into the layered meanings that human language achieves. In short: there are no wugs in the wild.

Significant progress in the conceptualization of what is humanlike about animal calls: recursion, compositionality.

Selected readings

- "Archive for Animal communication"

- "Archive for Animal communication", part. 2

- "The implications of chimpanzee call combinations for the origins of language" (5/29/25)

- "'Chimps have tons to say but can't say it'" (1/11/10)

- "Nim: the unproject" (8/16/11)

- "Seidenberg on Singer and Nim" *8/27/11)

- "Annals of animal communication" (10/20/10)

- "Chicken or egg; grammar or language" (1/16/25)

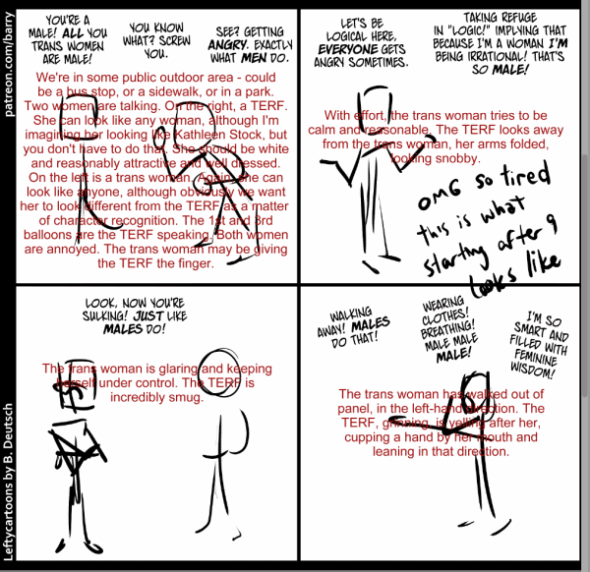

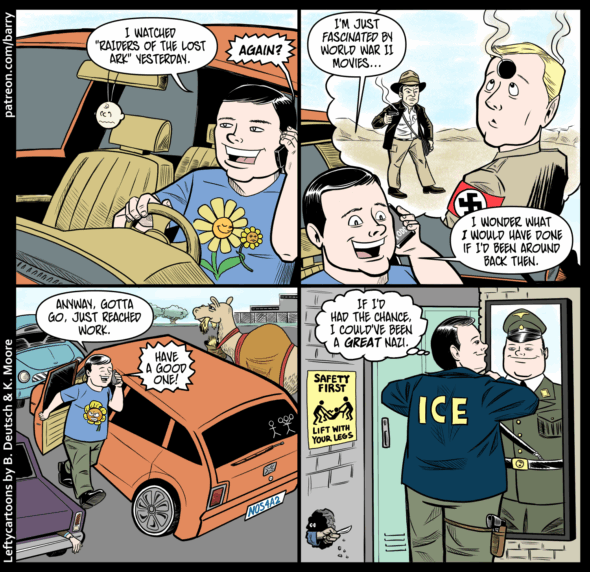

, I also remember acquaintances asking me “Which one of you is the guy in the relationship?” and dissecting my wardrobe, actions and mannerisms to figure out the answer. So I was ready to lampoon the labeling of human activities as “man” things.

, I also remember acquaintances asking me “Which one of you is the guy in the relationship?” and dissecting my wardrobe, actions and mannerisms to figure out the answer. So I was ready to lampoon the labeling of human activities as “man” things.